A Streetcar Named Desire is more than entertainment. It includes numerous social conflict undertones which give it relevance, depth, and meaning. Williams wrote in a way so as to pull at the hearts of those in the audience.

Through the play, Tennessee Williams:

Many of Tennessee Williams’s characters are individuals psychologically trapped in the myths, self-delusions, and pretensions of the “gentility” of the agrarian, “Cavalier” past. Some are of the Southern “wench” variety, passionate in behavior, sex-driven, and in conflict with Puritan/Victorian mores. Some of his male characters are lusty, self-serving “rednecks”; others are “poet realists” who try to find their way in the shifting economic profile, changed values, and altered morality of a new South. Yet others are dull, unimaginative types, representative of Williams’s view of those who have bought into the “herd mentality” of the American “shoe-factory” world. Williams’s primary genius, however, is in his ability to develop compelling characters that transcend the Southern environment in which they are implanted. The obsessed mother, Amanda, and her overly-shy daughter, Laura, in The Glass Menagerie; the fragile, “displaced” Blanche of A Streetcar Named Desire; the raw sexual energy of Stan in Streetcar and of Maggie in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; the vulnerability of Tom in The Glass Menagerie; and Mitch in Streetcar grow out of the embedded tensions of the post-Civil War South. But their problems and conflicts resonate deep chords of all human experience.

The link to the full article is below.

American theater grew out of the milieu of sweeping economic, political, social, and cultural changes that occurred in the last half of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth. The fallout of the Industrial Revolution and the shockwave of new psychological theories would resonate throughout American culture, making a strong impact on a burgeoning American population realigned by surges of immigrants, traumatized by war, and increasingly uprooted in the shift from a primarily agrarian to an urban/suburban society. Ironically, in their reach to clarify and give meaning to the turbulent changes of this “modern” world, American playwrights would draw heavily from the sources that had helped effect change. Experimenting in a symbiotic relationship with European writers and artists of other genres, American dramatists found inspiration in the intellectual “arguments” of Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, and Herbert Spencer, and especially in the psychoanalytic concepts of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. The vibrancy of the themes and forms of modern American drama resound with these influences.

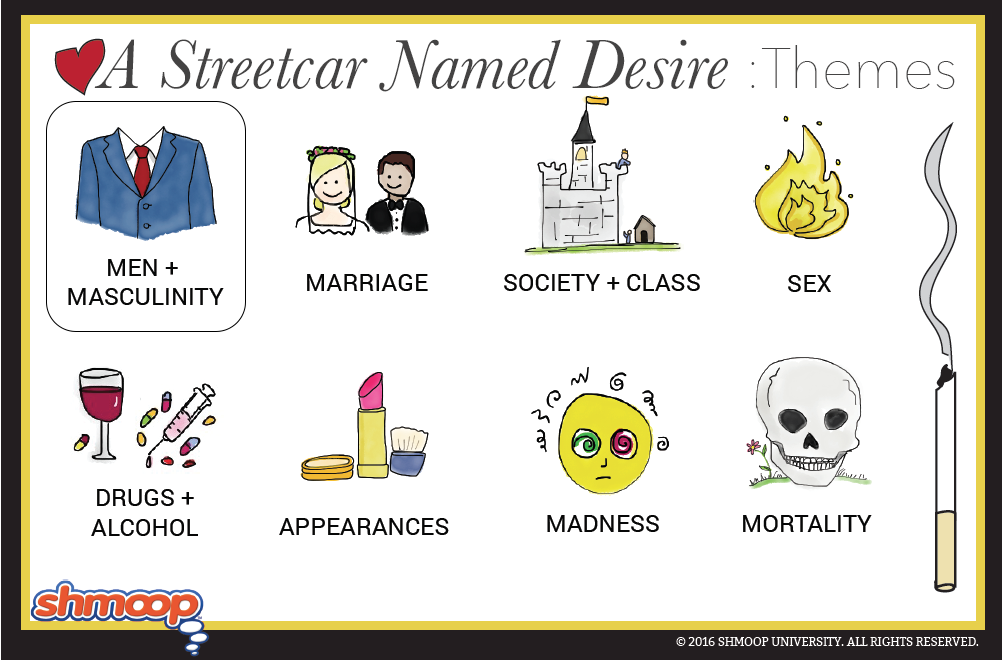

(Source: shmoop)

A major theme explored symbolically in Streetcar is the decline of the aristocratic family traditionally associated with the American South. These families had lost their historical importance as the agricultural base of the Southern states were unable to compete with the new industrialization. A labor shortage of agricultural workers developed in the South during the First World War because so many of the area's men had to be employed either in the military or in defense-based industries. Many landowners, faced with large areas of land and no one to work on it, moved to urban areas. With the increasing industrialization which followed in the 1920s through the 1940s, the structure of the work force changed further: more women, immigrants, and black laborers entered the workforce and a growing urban middle class was created. Women gained the right to vote in 1920 and the old Southern tradition of an agrarian family aristocracy ruled by men began to come to an end.

Symbolism is the use of an object, a person, a place, or an experience that represents something else, usually something abstract. A symbol may have more than one meaning, or its meaning may change from the beginning to the end of a literary work.

|

Light Bulb |

The "naked" light bulb symbolizes truth and reality. The light bulb also symbolizes an epiphany. An epiphany is an "a-ha!" moment, the moment when some new idea or concept occurs to a person. |

|

Paper Lantern |

The paper lantern symbolizes something flimsy that is used to disguise reality, create illusion, and hide the truth. However the paper lantern cannot last, it can only temporarily create a romantic glow and keep the truth in shadow. The paper lantern is used by Blanche to disguise her fading beauty and indecent past. |

|

White Clothing |

White symbolizes purity and innocence. |

|

Package of Meat |

The package of meat that Stanley throws at Stella and her eager catching of the the meat is a symbol of their sexual relationship. Stanley is the provider (hunter & gatherer) and Stella waits happily at home for his return. The meat represents Stanley's almost barbaric manliness. |

|

Bathing |

Blanche's constant bathing shows her need to cleanse herself (metaphorically) of the impurities and disappointments in her past (the Hotel Flamingo, her own sinful behavior with her young husband). The bathing helps relax Blanceh's nerves and allows her mind to imagine that she is in better (and more pampered) circumstances. Bathing also makes Blanche feel young and girlish, laughin, singing, and splashing in the tub like a child. |

|

Polka Music |

The polka music that Blanche hears whenever her young husband is discussed reminds Blanche of the frenzied manner in which she lost her husband. This music haunts Blanche and is one of the realities that she desires to escape. |