Great Britain made its first tentative efforts to establish overseas settlements in the 16th century. Maritime expansion, driven by commercial ambitions and by competition with France, accelerated in the 17th century and resulted in the establishment of settlements in North America and the West Indies. By 1670 there were British American colonies in New England, Virginia, and Maryland and settlements in the Bermudas, Honduras, Antigua, Barbados, and Nova Scotia. Jamaica was obtained by conquest in 1655, and the Hudson’s Bay Company established itself in what became northwestern Canada from the 1670s on. The East India Company began establishing trading posts in India in 1600, and the Straits Settlements (Penang, Singapore, Malacca, and Labuan) became British through an extension of that company’s activities. The first permanent British settlement on the African continent was made at James Island in the Gambia River in 1661. Slave trading had begun earlier in Sierra Leone, but that region did not become a British possession until 1787. Britain acquired the Cape of Good Hope (now in South Africa) in 1806, and the South African interior was opened up by Boer and British pioneers under British control.

Nearly all these early settlements arose from the enterprise of particular companies and magnates rather than from any effort on the part of the English crown. The crown exercised some rights of appointment and supervision, but the colonies were essentially self-managing enterprises. The formation of the empire was thus an unorganized process based on piecemeal acquisition, sometimes with the British government being the least willing partner in the enterprise.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the crown exercised control over its colonies chiefly in the areas of trade and shipping. In accordance with the mercantilist philosophy of the time, the colonies were regarded as a source of necessary raw materials for England and were granted monopolies for their products, such as tobacco and sugar, in the British market. In return, they were expected to conduct all their trade by means of English ships and to serve as markets for British manufactured goods. The Navigation Act of 1651 and subsequent acts set up a closed economy between Britain and its colonies; all colonial exports had to be shipped on English ships to the British market, and all colonial imports had to come by way of England. This arrangement lasted until the combined effects of the Scottish economist Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776), the loss of the American colonies, and the growth of a free-trade movement in Britain slowly brought it to an end in the first half of the 19th century.

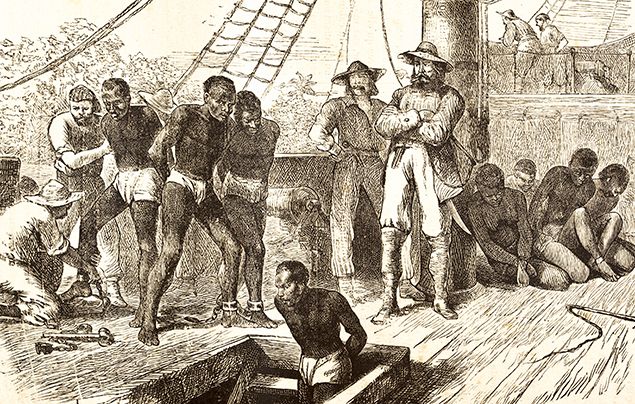

Enslaved persons on a West Indian plantation being freed following passage of the Slavery Abolition Act (1833).

The slave trade acquired a peculiar importance to Britain’s colonial economy in the Americas, and it became an economic necessity for the Caribbean colonies and for the southern parts of the future United States. Movements for the end of slavery came to fruition in British colonial possessions long before the similar movement in the United States; the trade was abolished in 1807 and slavery itself in Britain’s dominions in 1833.

Source: https://www.britannica.com/place/British-Empire

For people living in the colonies, British rule often meant that their traditional languages, religions and ways of living were replaced with the English language, Christianity and British systems of government and education. English remains the official language of many ex-colonies to this day. The number of speakers of some indigenous languages, like that of the in New Zealand, has declined dramatically.

The colonies were generally run by British government officials who lived in the colony and not by the indigenous people. British laws were brought to colonies that often did not take into account cultural differences between the people of the colonies and the British. Taxes on colonised people were often high and the British exploited natural resources for their own financial gain.

In the 1700s and 1800s, India experienced several devastating famines. These famines were partly caused by the weather, and the region had suffered from famine before British rule, but British policies often made the situation worse. Under British rule, Indians were pushed to produce crops, such as tea, that Britain could sell for high prices. Therefore when poor weather affected the harvests, there were food shortages resulting in famines across India. During many of these famines Britain did not organise a large enough relief effort, and millions died across India.

Punishments for uprisings and protest were harsh. They could include executing people and even firing openly onto crowds of civilians, for example during the Amritsar Massacre.

Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zpjv3j6#z449kty

From the 1750s onwards, there were huge developments in technology in Britain. New machinery and railway technology meant that goods could be produced and transported much faster. This reduced the amount of physical labour needed to produce goods and made more money for those in charge.

This technology was introduced in British India, which reduced the time it would take to transport large amounts of goods from India to the ports, and then to transport goods such as cotton and tea to Britain.

After introducing this in India, Britain introduced this same technology in other colonies. This technology was left in the colonies after they became independent.

Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zpjv3j6#zbmvbqt

While there was a lot of support in Britain for the empire at the time, there was always some opposition to it. Some people argued that colonies had their own cultures and traditions before the arrival of the British, and that it was wrong to force a different way of life or religion on people.

There was opposition to the transatlantic slave trade in Britain during the 1700s and 1800s. This came from members of parliament, like William Wilberforce, as well as religious organisations, such as the Quakers. Olaudah Equiano, a formerly-enslaved man who settled in London, campaigned against slavery and published an autobiography detailing his experiences of enslavement.

The opposition to empire became stronger when Britain went to war to protect its new power, as this often led to the deaths of indigenous people and British soldiers. For example, there was public opposition to the Second Boer War, as well as political opposition from the Liberal Party.

Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zpjv3j6#zbmvbqt

In the 16th Century, Britain began to build its empire – spreading the country’s rule and power beyond its borders through a process called ‘imperialism‘. This brought huge changes to societies, industries, cultures and the lives of people all around the world.

Empire is a term used to describe a group of territories ruled by one single ruler or state. Empires are built by countries that wish to control lands outside of their borders. Those lands can be close by or even thousands of miles away. For example, the Roman Empire (1st – 5th Centuries A.D.) stretched all the way from Britain to Egypt.

Throughout history, empire builders have introduced new people, practices and rules to their ‘new’ lands and used its resources for their own gain, at the expense of the indigenous people – the people that inhabited the land first. This process is called ‘colonialism‘. This was no different with the British Empire…

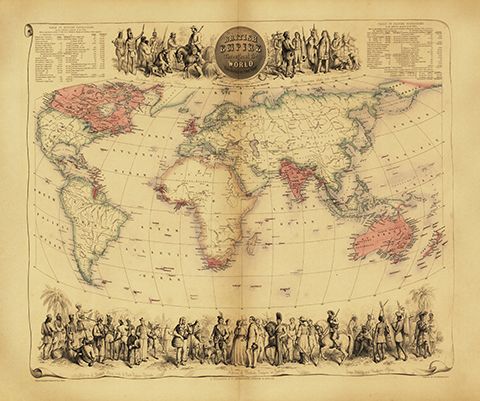

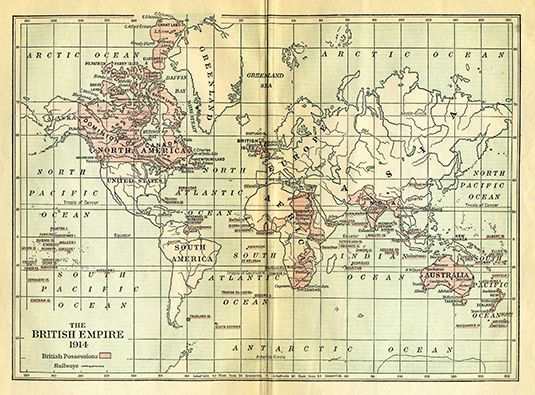

The British Empire is a term used to describe all the places around the world that were once ruled by Britain. Built over many years, it grew to include large areas of North America, Australia, New Zealand, Asia and Africa, as well as small parts of Central and South America, too.

How big was the British Empire?

The size of the British Empire – the amount of land and number of people under British rule – changed in size over the years. At its height in 1922, it was the largest empire the world had ever seen, covering around a quarter of Earth’s land surface and ruling over 458 million people.

Why did Britain* want an empire?

The 16th Century is often referred to as the ‘Age of Discovery‘ – new thinking about the world and better shipbuilding led to more exploration and the discovery of new lands.

England, in what is now Britain, wanted more land overseas where it could build new communities, known as colonies. These colonies would provide England with valuable materials, like metals, sugar and tobacco, which they could also sell to other countries.

The colonies also offered money-making opportunities for wealthy Englishmen and provided England’s poor and unemployed with new places to live and new jobs.

But they weren’t alone. Other European countries were also exploring the world, discovering new lands and building empires, too – the race was on, and England did not want to be left behind…

The first English colonies were in North America, at the time known as the ‘New World‘. Creating colonies was no easy task for the English! In 1585, the famous explorer Sir Walter Raleigh tried and failed to build an English settlement at a place called Roanoke in Virginia. It wasn’t until 1607 that Captain John Smith founded the first permanent English colony at Jamestown in Virginia.

Over time, the English would claim more and more territories. This sometimes meant fighting with other European nations to take over their colonies.

Over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, England gained major colonies in North America and further south in the West Indies, today known as the Caribbean Islands. Here, the climate was perfect for growing crops like sugar and tobacco, so they set up farms known as plantations.

Trading settlements were also created in India by a company called the East India Company. This company became so powerful, it allowed England to control of the trade of luxury goods like spices, cotton, silk and tea from India and China, and it even influenced politics.

The years 1775-1783 were a turning point in British history, as the nation lost a huge part of its empire in the American War of Independence. Feeling ‘American’ rather than ‘British’, and resentful of sending money back to Britain, 13 colonies in North America united and fought to be free from British rule. With the help of Spain, France and the Netherlands, they won the war, and gained independence, becoming the United States of America. This marked the end of what is now called the ‘First British Empire’.

Although Britain had lost a huge part of its North American territories, it claimed new lands in the late 18th Century and early 19th Century, forming the ‘Second British Empire‘. Colonies were founded in parts of Australia, and later Trinidad and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Singapore and Hong Kong (China) as well as other parts of Asia.

From 1881 to 1902, Britain competed with other European empire-builders in what became known as the ‘Scramble for Africa’. By the early 1900s, huge parts of Africa – including Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and large areas of southern Africa – all came under British rule. The British Empire was larger and more powerful than ever…

As Queen of Great Britain, Queen Victoria was also Queen of all the countries in the British Empire. She was even Empress of India! Here she is pictured on a Canadian postage stamp during her reign.

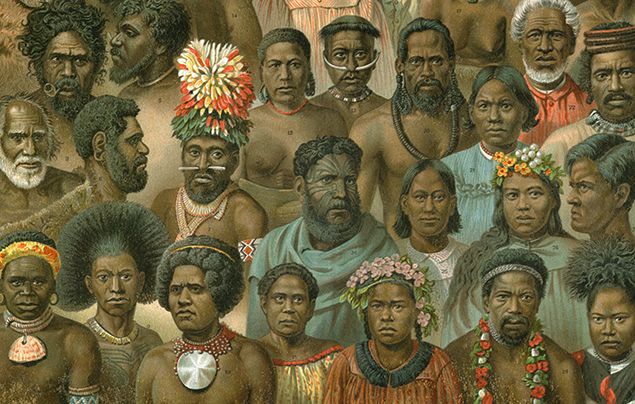

The power and wealth that Britain gained as it built its empire came at a price, and tragically, the price was paid largely by the Indigenous Peoples – tribes and communities who had lived in Britain’s so-called ‘new’ lands for centuries.

The unjust treatment of Indigenous Peoples ran the course of the British Empire. For example, in North America, local people were taken advantage of by greedy traders, robbed of their land and even faced violence and death at the hands of British settlers.

During the Second World War, India suffered some of the worst famines (lack of food) in human history, partly caused by the British government taking vital supplies away from the Indian people to support the war effort elsewhere – causing the death of millions.

Indigenous Peoples in Africa were affected in their millions. The British took valuable materials like gold, salt and ivory out of Africa and sent it back to Britain, and elsewhere. The British were also heavily involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade in West Africa – more on that, in the next section.

Many Indigenous Peoples, including Indigenous Australians, lost not just their land, food and possessions, but their traditions, too. When British settlers arrived, they forcibly replaced the beliefs, language and traditions of Indigenous populations with their own, removing their cultural identities.

Governments and settlers drew up new borders and land boundaries that split the local people into new countries and categories that didn’t represent them or reflect their heritage, history and customs. In some countries, these changes are still a source of conflict, even now.

Today, many Indigenous communities are trying to reconnect with the heritage the British tried to erase, by celebrating their cultural identities and protecting them for the future.

One of the most horrific parts of the history of the British Empire was its involvement in the trade of enslaved people – people who were made the property of others and forced to obey their owners’ demands.

Throughout history, slavery has existed on all continents and in many societies, but when the European imperialists arrived in Africa in the 15th Century, they began the most organised slave operation the world had ever seen – the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Over the next 400 years, European traders bought and sold an estimated 12 million African people, who were forcibly taken from their homes and shipped across the ocean to the Americas and Europe, where their buyers forced them to work.

Of those 12 million Africans, British slave traders are estimated to have bought and sold over 3 million people – although only 2.7 million are believed to have survived the journey – during which they were cruelly packed onto ships in crowded, dirty conditions. Many enslaved people were only children, like you, and were separated from their parents and siblings.

Slavery made Britain incredibly wealthy. It provided slave owners with unpaid labour to farm expensive items like sugar, tobacco and cotton, which they could sell for huge profits – at the expense of the enslaved people and their homelands. It also largely funded Britain’s Industrial Revolution, which only went on to make Britain richer.

Britain banned the trading of enslaved people in its empire in 1807, (known as Abolition) but it was a further 26 years until it outlawed slavery altogether (known as Emancipation).* Although, even when ‘free’, former enslaved people continued to suffer in racist societies. People considered them less important than white people, and used these beliefs to help them justify the former trading of enslaved people.

Even when slavery was abolished, former slave owners were paid compensation by the British government for the loss of their human ‘property’. No compensation was paid to the enslaved people themselves! The compensation sum was vast, and in fact, the loan taken out to pay for it was still being paid off by British tax payers as recently as 2015!

Many former slave owners went on to invest their compensation money in businesses – some of which still exist today – or in development projects like the British railways. Therefore, even though slavery had ended, its legacy continued to live on.

In fact, you can still see evidence of the profits of slavery in Britain today. Just take a look at the impressive 18th and 19th Century buildings that line cities like London, Liverpool and Bristol and the grand, stately homes in the British countryside.

Over the course of the 20th century, Britain’s empire broke down in stages. After the First World War (1914-1918) there was a feeling of ‘nationalism’ sweeping the globe, whereby countries should have the right to be independent and rule themselves. In 1926, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa became independent, meaning they were no longer under British control.

So, why were these countries given independence first? Well, by this time these countries had large white populations of European descent, living under the rule of formal governments. They were therefore considered to be more experienced and ‘able’ to run their own country successfully, which would benefit the empire as a whole. Racist views held by the British at the time meant that other British colonies – with large populations of non-white people – weren’t granted independence, even when they asked for it…

Over the next decades, however, the remaining colonies continued to push for independence. After the Second World War, Britain no longer had the wealth or strength to manage an empire overseas. Many colonies had fought for the British during the war (although people of colour were mainly given low-rank positions), and were making their own plans for independence.

In 1947, India won its independence, and from the 1950s to 1980s, African colonies also fought for and won their independence. The last significant British colony, Hong Kong, was returned to China in 1997. What had taken hundreds of years to build, was broken down far quicker!

That said, there are some small fragments of the British Empire that still exist today, known as ‘British Overseas Territories’. These are mainly self-governing countries separate to the United Kingdom, that continue to share a bond with Britain. They include Anguilla, Bermuda, British Antarctic Territory, British Indian Ocean Territory, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Monserrat, Pitcairn Islands, St. Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and Turks and Caicos Islands.